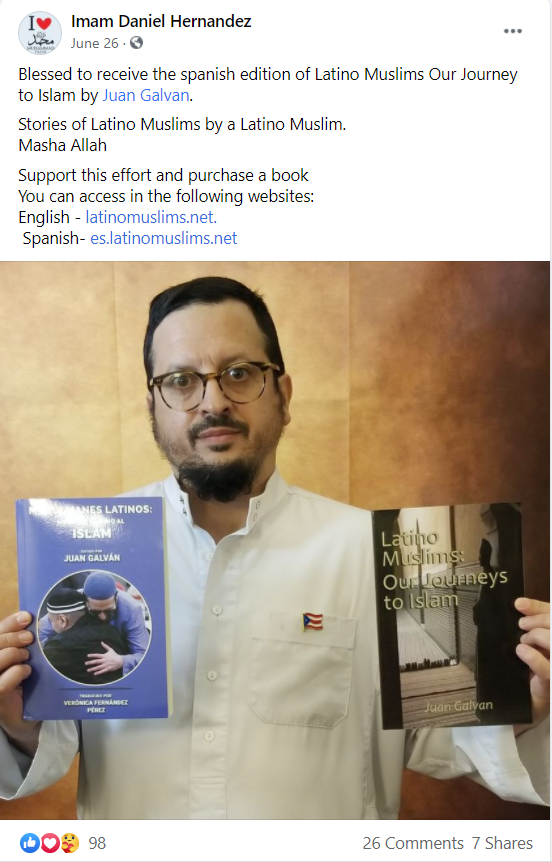

Check out what Imam Daniel Hernandez of 3puertoricanimams.org posted on Facebook.

You can buy the Spanish translation of my book on Amazon.com.

Check out what Imam Daniel Hernandez of 3puertoricanimams.org posted on Facebook.

You can buy the Spanish translation of my book on Amazon.com.

As a light-skinned (Chicago winters will do that to anyone) Mexican-American, I have often had to deal with the frequent ‘you don’t look Mexican’ comments. Now that I am also Muslim (13 years & counting), I am more often mistaken for being Arab or Bosnian, so I actually blend in at the mosque. But when people find out I’m Mexican, they then ask the question ‘wait, how can you be Mexican and Muslim?’

Part of the issue for people not being aware of our presence has always been that the greater Latino/a community does not do a good job of marketing our stories. This is not totally our fault because Hollywood has not deemed us important enough to be featured in movies, even though we make up more than 30% of the movie-going audiences. Latinos/as have been even further delegitimized over the years when white actors simply put on brown face (ala West Side Story) to play Latinos/as or just chose non-Latino/a actors and actresses (an actor like Lou Diamond Phillips should thank Latinos every day for his roles) to play the roles of Latino/a characters. So it is not surprising that Latino/a Muslims are not a very well-known community since the larger community’s story is already not being told.

The importance of the book ‘Latino Muslims: Our Journeys to Islam’ is rooted in the fact that the Latino/a Muslim community deserves the opportunity to share our stories with the world. Too often our stories are left unheard and this is sad to me because I know how much can be learned through the personal narrative. One can theorize for years about the reasons a group of people may be embracing a new religion, but if that same group of people is given the platform to speak and present their stories, it is so much stronger and impactful.

Take for instance the story of Ricardo Pena. His path to Islam was one that included a thirst for knowledge that started with simply reading the daily newspaper on the bus on the way to school each day. But eventually, it led to his further desire to know about various religions in a search for his own truth, finally leading him to Islam. His story holds a common thread amongst many converts to Islam, the desire to know truth and have a personal connection to a faith that just feels right, feels like home. This book is hopefully the start of many narratives to be written about Latino/a Muslims and I pray that it is one that opens the eyes of many people to the often courageous, uplifting and emotional journeys many of us have taken in our spiritual paths.

Aaron Siebert-Llera, Esq. is the Staff Attorney for the Inner-City Muslim Action Network.

From: Why the stories of Latinx Muslims matter

This text, which I turned to in its draft form as a website and blog during my master’s research, not only presents general comments on the place of Latinx Muslims in the American Muslim story, but it also does the simple, but significant, service of presenting scores of stories from Latinx Muslims themselves. Readers listen to men and women from across the Americas who identify as Latina, Latino, Latinx, Hispanic, or Spanish-speaking tell their stories of reversion (or ‘conversion,’ Latinx Muslims refer to their conversions as ‘reversions,’ both because they believe in fitra — that human beings are born with an innate inclination toward tawhid [the oneness of God] and draw on their Andalusian roots to speak to the very Arab and Muslim basis of much of Latinx culture, language, and history).

Readers will enjoy how Galvan frames these narratives with his own historical, theological, and cultural commentary, but will be most impressed by the sheer diversity of stories and experiences of those who converted in prison or on their front porch, to those who reverted in Australia and Bolivia, and those who found Islam on Facebook, through Latinx specific organizations, their future spouses, in dreams, or even while smoking weed and drinking a 22oz. of Heineken. Not only does this text do well to let the stories stand for themselves and permit Latinx Muslims’ voices to be heard above all else, but it also provides a wealth of primary data for researchers and interested students looking to learn more.

January 5, 2018

The precise value of religious conversion narratives has been an issue of minor debate in scholarly circles. Although it is agreed that such narratives provide the scholar with useful information, just what information they are providing is uncertain. Like all forms of narratives, conversion narratives are crafted by an author at a particular time and place, and, even when not consciously acknowledged, they are written for a particular audience. Conversion narratives can therefore be influenced by a myriad of factors: the amount of time that has passed since the conversion; the convert’s mood when writing his or her story; what he/she has read, watched, listened to, and discussed with others; how many times the narrative has been told; the religion and ethnic group the audience is expected to be; the writer’s skill as a storyteller; the amount of time the convert has spent writing the narrative; the culture in which the narrative is given—the list could go on. To make matters even more complicated, in cases where conversion narratives are compiled together, since A) the authors did not follow the exact same format and B) the reader is rarely given detailed biographical data about each author or any information about how the narratives were selected, despite one’s desire to compare the narratives, it is difficult to draw many strong conclusions, and scholars are right to avoid using them uncritically. For these reasons, although published collections of conversion narratives are generally fascinating and informative, scholars should use them with extreme caution.

All that being said…While I was working on my books on early white and African American Muslim converts, I had very few conversion narratives of my subjects and in my most frustrating periods I secretly hoped I would somehow stumble upon a previously unknown collection of first-person stories about the religious journeys of early American Muslim converts. Such a book would have made my research that much easier and would have provided that much more depth to my descriptions and analyses. In the end, I was able to find a small, little-known book of narratives written by several early members of the Nation of Islam—although it was only of limited value for my project, due to the book having been published nearly 60 years after the Muslims’ conversions and their narratives, as a result, lacking a great deal of information on their religious transformations. To this day, then, I still on occasion long for narrative collections by early Muslim converts so that I can fill the gaps I know exist in my histories. So, despite all the limitations of conversion narratives, especially collections, I admit that, given certain situations, they can be a goldmine.

But what about conversion narrative collections from the contemporary period—a time when hundreds of Muslim converts’ life stories have been collected and published, often by scholars and grad students in ethnography, psychology, and history departments? And what about cases where many of the narratives had already been placed online so that anyone could freely access them? When Juan Galvan, the editor ofLatino Muslims: Our Journeys to Islam, approached me to get my opinion on the potential scholarly interest in such a collection, I was up front with him concerning my doubts about it. I explained, in short, that in today’s scholarly world, scholars would appreciate it but we would rather have direct interviews and surveys. This, in my opinion, would be particularly true for scholars of Latino Muslims, since there are only a handful of them and I assume that most of them have already read and analyzed many of the Latino Muslim narratives that are online. (I know I had analyzed 28 such narratives for a speech at a regional American Academy of Religion meeting while I was in grad school.) Given all of this, I said, a book like the one he was proposing would be of most value to other converts and potential converts, not scholars. When Juan then informed me he had already completed the project and that he’d like me to review it, I feared that I would not find much new scholarly value in it.

It turns out, however, that I was wrong. Galvan’s collection of conversion narratives will make an important resource for scholars who examine Latino Muslims. As already mentioned, a number of these narratives are presently online, but they are scattered across multiple websites and numerous subsections within those websites—and sometimes buried as single articles in long, one-page publications. Galvan’s book has made it significantly easier to find these narratives. In some cases, though, the narratives were not previously available on Galvan’s various Latino Muslim webpages—or at least they were buried deep enough in a salad of hotlinks that I was unable to find them. The book’s most significant contribution, though, is the sheer number of narratives, 52, which, as far as I am aware, makes this the single largest book collection of narratives of American Muslim converts of any ethnicity ever to have been published, slightly edging out Steven Barboza’s important 1993 collection American Jihad: Islam after Malcolm X.

And, like Barboza’s collection, Galvan’s book features both community leaders and “regular” people, offering the reader access to a rich variety of stories coming from individuals whose Latino identities and experiences vary considerably. The diversity of the converts can be appreciated by just looking at the list of some of the countries they are from, in which they have lived, or to which they trace their ancestors: Canada, Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, the Dominican Republic, Germany, Cuba, Puerto Rico, Italy, Syria, Saudi Arabia, the Philippines, Mexico, England, El Salvador, Peru, Australia, and the United States. The life experiences of these individuals are diverse as well; the book tells the stories of immigrants and the US-born, those from broken homes and those from loving families, ghetto dwellers and farmers, soldiers and students, atheists and devout Catholics. For those who have studied new Muslims in America and are familiar with many of the common reasons that people in the United States have embraced Islam, it is striking that, although one could group similar narratives together, no two stores in the four dozen here are the same, which reflects the wide variety of cultural, psychological, spiritual, and even discursive currents that are at play as people across the country turn to Islam.

It is of course still true that a responsible scholar should not simply and uncritically take conversion stories at face value, and it is the things that this book lacks that will make a critical scholarly analysis of its contents all the more important. The reader, for instance, is not provided with any data about the converts beyond what they have chosen to include in their narratives—narratives that occasionally do not give any clue as to the convert’s location, mosque affiliation, age, or nation of (family’s) origin—basic pieces of data that would significantly aid analysis. The sources of the narratives or the dates they were written are also not included, nor is, in most cases, information given that might indicate whether or not the convert has written or told his or her story before—and how similar or dissimilar their narratives are compared with other converts they personally know. This type of information can be of immense help in determining larger issues concerning patterns of conversion, geographic dynamics, and discursive movements. More research will therefore be necessary to uncover such trends.

Still, Latino Muslims: Our Journeys to Islam can be of real value to scholars of American Islam and Latino religions. It has ensured, first of all, that these narratives have been both preserved and made easily accessible; no longer will their fates be dependent solely on the upkeep and viewership of old websites and tortuous hyperlink chains. Scholars who read this book will be forced to acknowledge the diversity and breadth of the Latino Muslim experience—conclusions based on small samples of respondents will not suffice. Finally, for those who look hard enough, there are enough clues in this book that one can begin to connect dots to other known events in the histories of Islam in America and Latino religions. Latino Muslims, then, is essentially the type of book I was hoping to find when I was working on early white and African American Muslims—and I am sure the other scholars who find it will similarly recognize it as the gem that it is.

Latino Muslims: Our Journeys to Islam will be available online at Amazon.com in paperback and digital versions and in hardcover at BarnesAndNoble.com. ISBN: 978-1530007349. Publisher: Self-published. Page Count: 243. See also: http://www.latinomuslims.net/

Check out these recent reviews left on Amazon.com.

“Here is a book that will fill your ears with a chorus of voices you may never have heard so clearly. What I love about this carefully introduced, large collection of testimonial essays is its variety, its unsettledness, its openness, its range.

One the one hand, readers who know little about Islam and its history will be surprised by the very idea of Hispanic-rooted converts to Islam. They should get ready for some reminders: that Spanish is full of Arabic words, that the architectural resemblances between Mexico, say, and the Middle East are not accidental, that Spain, the social, cultural and intellectual pearl of medieval Europe, was full of Muslims from Mecca, Damascus, and Morocco for at least eight centuries, that large numbers of Roman Catholic and secular people now living in Spain and its far-flung New World ex-colonies may, if they like, trace their lines back to Muslim families of centuries ago— and that Jesus has always played an essential role in Islamic theology and Muslim life.

On the other hand, Muslims who know all these things may be surprised by Juan Galvan’s book too, because the voices here don’t pull punches or smooth over the problematic aspects of taking up a new religion by choice. Our Journeys is a collection of actual, living human voices reveling in the beauty of discovery but also grappling with the stresses and strains of a decision that may easily confuse neighbors and even, perhaps especially, close relations. Get ready for the sort of wild ride that only truth-tellers take you on. Sometimes religion can get in the way of truth-telling. Not in this case.”

Praise by Michael Wolfe, the author of “The Hadj: An American’s Pilgrimage to Mecca.”

The narrative of a minority within a minority, this collection of stories fell on my lap after Juan Galvan had introduced his project which immediately drew my interest.

The book’s very first outstanding feature was its humble character. Each story spoke of truth seekers of all walks of life, from a student and a military man to a college professor and an internationally acclaimed writer. Yet, they all shared with a stunningly equal awe and just as equal piety.

Another feature was the book’s vast range of emotion. Several testimonies were filled with heart wrenching details of a human tragedy, others with human joy and celebration.

One story takes you on a trip to see the world; another tells you what happens at your backyard. Men and women open up about their failures and their achievements, and before you know it, you are walking to the minarets, listening to the muezzin and tasting a day of Ramadan.

This book will make you cry, laugh, contemplate, feel empowered and peaceful. It’s an excellent introduction of role models to a younger generation of Muslims, and it’s a wonderful message of tolerance, respect and dialogue in a multi-cultural, multi-dimensional American and global society.